A people without the knowledge of their past history, origin and culture is like a tree without roots. – Marcus Garvey

Stephen Towns has learned about his past history, his origin and the depth of his culture through his art. A talented painter and fiber artist, he was born in South Carolina in 1980, began drawing as a child and continued on a creative path at the encouragement of his mother and sister. Studying painting at the University of South Carolina (USC) in the early-2000s, a professor introduced the young artist to the Dutch Golden Age painters and Renaissance masters, which strengthened his interest in figurative art.

The subject of labor became an important part of Towns’s practice a few years after earning his BFA in Studio Art from USC. Losing his job during the economic downturn of 2008, he decided to migrate north to Baltimore, where he remained unemployed for another two years. Finally finding a job at the Maryland Institute College of Art, however, put him in a position of observing its emerging artists and seasoned faculty, which helped set him on a course of becoming the artist he is now.

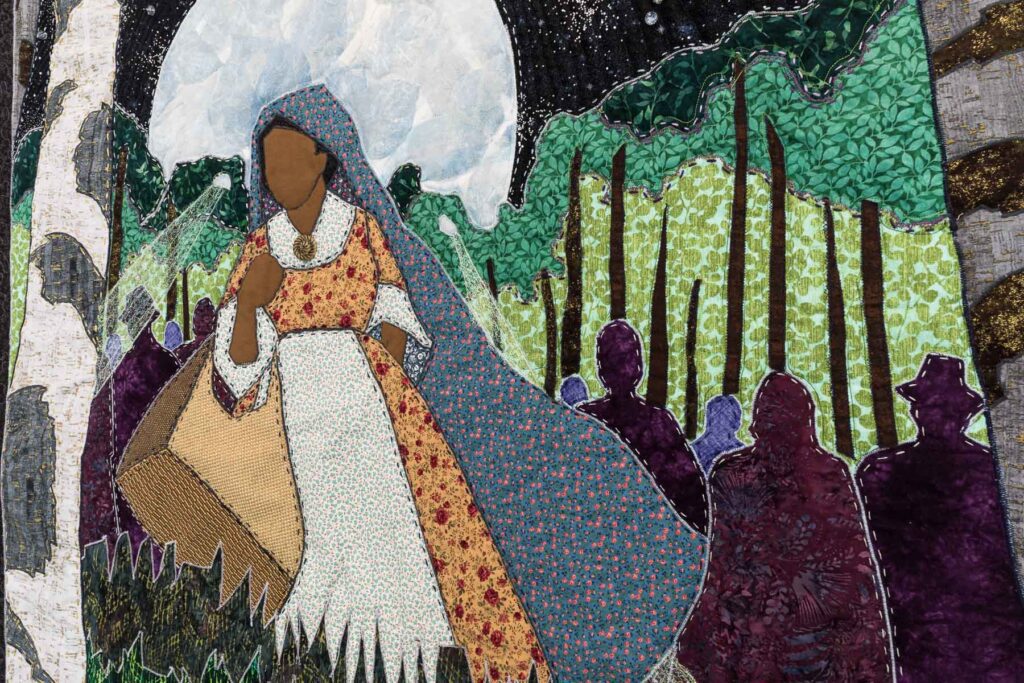

Ironically, Towns dates the emergence of his mature artwork to his 2014 fiber work Birth of a Nation. Wanting to make a textile work of a Black woman nursing a child against the background of the original 13-star flag but unable to find a suitable one, he decided to create his own. Watching You Tube video tutorials, he taught himself to quilt. Captivated with his new medium, in 2016 Towns began a series called Nat Turner Story Quilts, which grew during the next three years to nearly a dozen narrative artworks about Turner, the educated Black slave who led a rebellion of enslaved Virginians against their White masters in 1831. Employing his mother’s old clothing and found bits of fabric—the only materials that he could afford to utilize at the time—he stitched together a researched account of Nat Turner as he imagined it to be.

“Stephen is bringing traditional modes of quilting into a contemporary art dialogue,” Pittsburgh-based art historian and curator Kilolo Luckett recently disclosed when discussing his work. “He sources a variety of materials from many different places to create these very compelling stories.”

Over time, quilting—a form of storytelling on par with painting, but a more abstract, less detailed one—helped bring about a loosening of the artist’s way of painting. And with the addition of an Impressionist influence—particularly one inspired by Mary Cassatt, one of his favorite painters—to his more classical approach, his brushwork became freer and his forms more painterly, as seen in his compelling Black Magic series of paintings, based on religious and historical tales, realized in 2016.

With this new two-pronged approach, Towns continued to simultaneously create quilted works and mixed-media paintings. In his 2018 The Gift of Lineage, he combined his use of African fabrics found in the United States and gathered in Ghana with painting and metal leaf (a material that he had been using to simulate halos) to create striking pictures of strong forebears. For his series An Offering, he painted the upper halves and quilted the lower parts of the mixed-media works.

Part of the permanent collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington DC, where the pieces are currently on view, the works in An Offering commemorate enslaved African ancestors who didn’t survive the Middle Passage. With the artworks’ shapes mimicking the outline of an 18th-century British slave ship, the haloed predecessors—portrayed on gold-leaf backgrounds and surrounded by butterflies (a trope Towns took from a scene in the 1998 film Beloved)—are reflected in the ocean waters as hands holding fiery candles make an offering gesture of gratitude and solace.

Towns continued his hybrid mix of quilting, collage and painting in his powerful 2020 Coal Miners Series, which was his first group of paintings to solely focus on laborers. Painting portraits based on archival photographs of coal miners, who have one of the most dangerous jobs in the world for the lowest amount of pay, the artist created their soiled coats from fabric tinted with graphite and charcoal and poetically swapped his signature butterflies for canaries. Adding mica to the blackened backgrounds to get the effect of coal reflecting light, he dangled the image of an American flag in the paintings to signify the role that these workers had played in our nation’s development.

“When I look at an archive image, the person tells me something,” Towns shared in a recent conversation about his work. “It’s a communication between me as an artist, the photographer as a portraitist and the person being documented. Whatever the person is telling me in their eyes and their pose, I try to convey it in the work.”

For his solo traveling exhibition, “Stephen Towns: Declaration & Resistance,” which launched earlier this year at the Westmoreland Museum of American Art in Greensburg, Pennsylvania, Towns expanded the series to include other types of laborers. For his show, he collaborated with the exhibition’s curator, Kilolo Luckett, who suggested subjects and introduced him to the archive of Black photographer Charles “Teenie” Harris. Harris had chronicled the lives of African-Americans in Pittsburgh from the 1930s to the 1990s. Ranging from quilt pieces of such historical Black figures as Ona Judge and Marcus Garvey to paintings of anonymous nurses, soldiers and crossing guards, “Declaration & Resistance,” which has its final stop at the Reynolda House Museum of American Art opening February 18, 2023, examines the American dream through the lives of Black Americans from the late 18th century to the present time.

“I remember working in retail stores and being a waiter in a restaurant,” Towns added when we spoke. “I often felt down and defeated, but there were times when I felt proud of what I was doing. I wanted to take these moments of pride in myself and use that glimmer and that spark to create the work that I made for this show.”

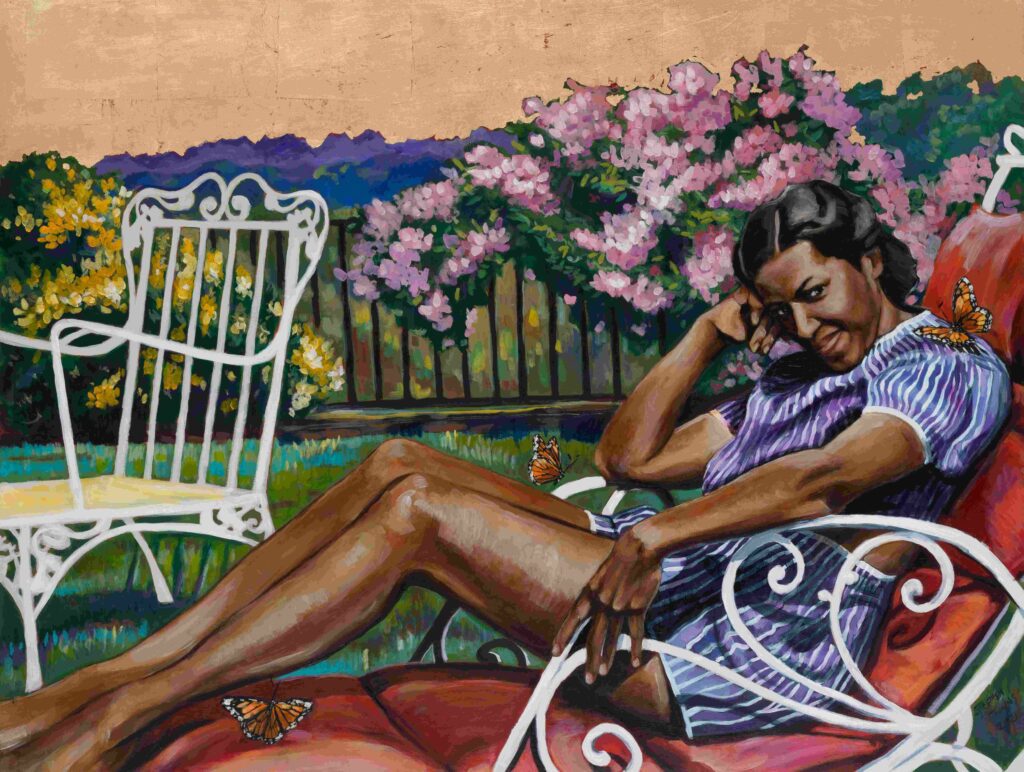

Creating many of the quilts and paintings in the show while isolated in his Baltimore studio during the pandemic, Towns continued the series in 2021 while he was an artist-in-residence at Fallingwater, the modernist house that architect Frank Lloyd Wright designed for Edgar and Liliane Kaufmann outside of Pittsburgh in 1935. One particular painting that he made there, titled Elsie Henderson, has a direct relationship to Fallingwater. Based on an old photograph of Henderson, who had worked at the Kaufmann Department Store in Pittsburgh before becoming a cook at the family’s retreat, the artist’s painting captures a young Henderson, who lived to the grand age of 107, happily reclining on a red chaise longue surrounded by the flowers she loved while being watched over by three migratory monarch butterflies.

Dealing with the same subject matter, “Stephen Towns: Glimpses of Americana,” his show currently on view at De Buck Gallery in New York, features 13 quilts and paintings. The audience now has the opportunity to consider his works on labor, resilience and leadership in relationship to such contemporary artists as Faith Ringgold, Kerry James Marshall and Isaac Julien, who share similar social interests and storytelling styles.

“Stephen is very meticulous, very detailed about things,” said Luckett. “There is so much that goes into his art-making that once you see it and spend time it starts to reveal itself.”